Thus they even carried the sick out into the streets and laid them on cots and mats so that when Peter came by, at least his shadow might fall on one or another of them. (Is 50:6:7)

There are two kinds of shadow. The first gives respite from the hot sun. This is what we simply refer to as “shade” and Jonah, while in Nineveh, was very glad for its presence and angry at its loss (Jon 4:6; 8-9). The other type of shade is metaphorical as in J.R.R Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, where the preservation of light (goodness) was threatened to be overcome by the shadow of darkness (evil). Hence, trees cast shadows providing relief from the heat; but the devil also casts his shadow upon a world that should quake in fear if not for the redemptive act of Jesus Christ.

The psalmist also presents this dichotomy of shadow. In Psalm 23 he speaks of the “valley of the shadow of death” which the psalmist would rightly fear if God was not with him with his rod and staff of comfort (Ps 23:4). Psalm 23 offered the Israelites a glimpse of hope, a prophetic consolation until the coming of the Christ.

Yet, the psalmist also speaks of a shadow of blessing in Psalm 17. Here God Himself is our pleasing shade, our “refuge from… foes” (Ps17:7). The psalmist is overjoyed for this kind of shade as he asks God to hide him “in the shadow of [his] wings” (Ps 17:8). The psalmist finds in this shade protection from his enemies.

We Christians know that the greatest and last enemy is death (1 Cor 15:26). Fortunately we have the soothing message of St. Paul that Christ comes to destroy the shadow of death. (Still, it is good that we remember that this shadow remains for those who utterly reject God’s divine mercy and show no mercy themselves – Mt 18:30-35).

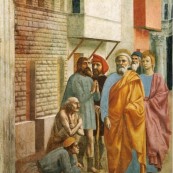

Thus, on this Divine Mercy Sunday we have placed on our bulletin cover a work by the great Quattrocento, Florentine painter Masaccio entitled St. Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow. Masaccio ushered in the Early Renaissance and like Giotto is another example of how the medieval gothic style transitioned organically into the renaissance through artistic progression (not through radical reformation as some would claim) especially shown in Masaccio whose early works were Gothic triptychs and sacred icons. Masaccio was one of the first Italian painters to master light and perspective; and emotion through posture and expression.

In our art piece taken from today’s first reading, Peter appears almost cold and uncaring in appearance as he passes the on-looking sick and immobile. But we must recall the transitional art of Masaccio and that he was painting in two styles. If you cut out the image of St. Peter and set it alone it would appear statuesque. This is the sacredness of the Gothic. Next we have attentive figures who await Peter’s healing. This is the naturalism of the Renaissance. These latter figures are active venerators of Peter’s shadow which is cast as God’s grace on the lame man sitting on the ground. No doubt this fresco inspired young artists with hope in the novel style. Yet, it also inspired eager Christians with hope for a glorious healing.

-Steve Guillotte, Director of Pastoral Services