Jesus bent down and began to write on the ground with his finger. But when they continued asking him, he straightened up and said to them, “Let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.” (Jn: 8:6-7)

The biblical narrative of the adulteress who was brought by the scribes and Pharisees before Jesus for judgment is (in the gospel of John) a brief but profound story. St. John related this story not only to instruct his readers about how Jesus was tested and pursued by the Jewish leadership, but also as a lesson about divine absolution. It is true that the Pharisees had earlier sent some officials to arrest Jesus (Jn 7:32). It is also true that the Pharisees even imputed one of their own, Nicodemus, for listening to Jesus (Jn 7:52). These are important points as John prepares to relate the Passion of Christ. However, this story is not only about the growing conspiracy against Jesus; it is also about the developing science of sacramental forgiveness.

Notice that the story does not follow the normal sacramental order of Confession: examination of conscience, firm purpose of amendment, confession, penance, and absolution. Yet, all parts of the confessional experience are present. First, the woman was caught in adultery and so the confession comes rather as an accusation. This is how we should all approach confession – as if caught in the act and exposed to accusation before God. Next comes the demanded penance which Jesus forgoes for now in place of the examination of conscience – not only for the adulteress, but also for her accusers (the practice of which thankfully curtails their own sin of murder). Finally, Jesus forgives the adulteress by way of His divine omniscience; for he graciously perceives her sorrow and her intent to amend her life. Lastly, underlying this science of reconciliation is its unspoken vital principle for all absolution: that in order to be forgiven, one must be willing to forgive others (Mt 18:33-34).

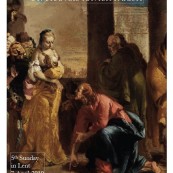

To recall this wonderful narrative of divine forgiveness on this 5th Sunday in Lent, we place on our bulletin cover a work by the Venetian Rococo painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo entitled, Woman Taken in Adultery (courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum). Rococo was a highly decorative style expanded from the Baroque, and Tiepolo was one of its masters who painted ceilings and other frescos with ornate religious, classical, and allegorical themes.

We are only able to show the central portion of the painting. We see a Pharisee standing behind the woman with his hand up as if to hail Jesus’ authority when in truth he has come to undermine it. Tiepolo creates an invisible diagonal, an interlocking “look” between Jesus and the Pharisee which visually goes through the woman. Absent is the force of any stone throwers while Jesus Himself is presented forward-kneeling on left leg as one able and ready to pounce forward in defense of the lady. This may also be why the Pharisee appears with docile bow, hiding behind the woman from the strong justice of Our Lord.

Now our adulteress may not be the guiltless Susanna protected by Daniel (Dn 13:48), however she has, as every repentant sinner does, the merciful protection of Jesus Christ.

–Steve Guillotte, Director of Pastoral Services