The Lord God took Abram outside and said, “Look up at the sky and count the stars, if you can. Just so,” he added, “shall your descendants be.” Abram put his faith in the LORD, who credited it to him as an act of righteousness. (Gn: 15:5-6)

When God spoke with Abram and promised him a great reward, Abram responded that a reward or gift would be pointless since he had no children on whom to bestow it; and Abram was already aged. God responded that the gift he would give to Abram was in fact an abundance of children down to many generations. Abram (eventually named Abraham by God) thus becomes (through his wife Sarah) the father of Isaac, who becomes the father of Jacob, who becomes the father of the nation of Israel. But this is not all that God intended.\

St. Paul elucidates God’s promise to Abraham not in terms of offspring, but in terms of faith. He recalls God’s other promise to Abraham – to make him the “father of many nations” (Gn 17:5) which at the time the promise was sealed was the exact moment God first called the once pagan Abram, “Abraham”. Paul explains that Abraham becomes a father through faith (Rom 4:16) and thus the “father of us all” who come to God through faith. The essential promise that God made to Abraham was to create the Church: the People of God, through Abraham’s example of faith.

We might wonder why God did not become angry with Abraham when he questioned the efficacy of God’s gift. It is because it was an entirely unselfish inquiry. A “reward” appeared meaningless to Abraham without its perpetuity; without it being able to be shared with those who would come after him. Abraham could have bequeathed God’s gift to those outside his family – to a servant not of his household (Gn 15:2) – but symbolically and mystically this gift would not have led to the spiritual household God intended: the household of the faithful which would adhere to the commands and love of the Son of God (Rom 4:24).

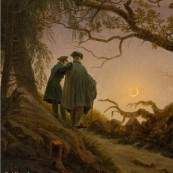

In order to commemorate the meeting between God and Abram, we place on our bulletin cover for this 2nd Sunday in Lent a painting by the German landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich, entitled Two Men Contemplating the Moonlight (1830). Friedrich painted in the Romantic style which reacted against the classical method. The Romantics believed the classical style to be too preoccupied with convention which could not properly and profoundly allow man’s free reflection upon nature. We, however, use this piece by Friedrich to create a visual allegory, not for a scrutiny of the natural, but of the supernatural: the spiritual contemplation of that intimate covenantal moment between God and Abraham.

Here God is represented in angelic dialogue as he leans slightly bent upon Abram’s shoulder. He is bent to show that God is of-old and wise beyond all ages; even his creation, the trees and rocks, bend in honor of his eternal presence. Abram however is represented rather straight and still as one held back in stasis until the future of faith comes to life fully in the Holy Spirit. God shows Abraham his future – which is us: we who believe in Jesus Christ.

-Steve Guillotte, Director of Pastoral Services